Kajiji

by Humphrey Odero and Zhuangchen JJ Zhou

Off the paved path to Lenana School in Nairobi, Kenya, stand rows of iron-sheet-walled homes -- the informal settlement of Kajiji. Shallow trenches of blue-green sewage water cut through the mustard-colored ground, running in front of the rotten and half-broken wooden doors of these homes. Lines of drying jeans, shirts and bed sheets under the tropical sun conceal the residents and their lives from outsiders’ eyes. In the deep shadows live women struggling with pain and disparity, and the lack of access to general medical and palliative care.

In the neighborhood of Kajiji, northwest of Nairobi's center, any sort of public facilities remain unseen. There are a green Mpesa (mobile money) hut, a water tank that provides fresh water for the entire neighborhood, and some fruit vendors. Beyond the settlement, a clinic near Ngong Road is about a fifteen-minute walk away. But the clinic cannot provide for those who are facing painful diseases. They would have to make their way to Kenyatta National Hospital, the major public hospital in the country. For an ill-troubled woman who also has to attend to children and housework, they would have to suffer through the noisy and recklessly-driven buses that sometimes run up to 100 Kenyan Shillings for a round trip. For a family living in Kajiji, that is the budget for a few days of groceries. And a trip to KNH does not guarantee a relief from the pain, given the cost and short supplies. While hospice care, and its emphasis on palliative care, is starting to grow in Kenya, many still do not know how to access the support and help they need. Poverty. Stigmatization. Pain. All are barriers to relief. It is in such troubled situations, these women suffer and struggle to survive.

Carol

Carol squeezes half of herself through a faded,-cyan-tinted wooden door, swings the door against her body and drags herself into her home slowly. Inside is a four meter by four meter room, with a double bed taking up half of the room, a couch the door hits when it opens, and a wooden table where dishes and avocados rest.

Carol has been supporting her two children with odd jobs here and there. This uneasy life became even harder when she discovered that she had contracted HIV from a boyfriend last year. Among the challenges that came with the diagnosis is caring for her oldest son, Miguel. When he was four-months old, Miguel had surgery for scoliosis. Due to complications, he was paralyzed from waist down. For the last nine years, Carol has carried him everywhere, and taken care of everything for him. Now the pain caused by HIV and the ARV drugs is so severe that she can't manage his care anymore. “I have to be massaged all the time. My babies do that. No trained people (from the hospital) would help me,” she says.

Carol developed reoccurring bumps below her abdomen that cause her pain. She went to a private hospital for help. There, the doctors shaved off the bumps, but they came back. They did not tell her what they are or what she can do to prevent or treat them. The doctors also did not give her any medicines that would alleviate her pain, pain that is so severe that sometimes she has to lie in bed unable to take care of her children for two weeks at a time.

Miguel has been sitting outside for the good part of the day. Carol looks at him from inside, her round eyes filling with tears. “It is so painful. You don’t have work; you can’t change your baby’s diaper; and you still have to pay for your house and pay for your children’s food. Pain for me is when people look at me like a criminal; when people say that I have a bad disabled son; when my children are dirty.”

Hannah

Enter an iron-sheet gate, walk through a front yard cluttered by old furniture, and one enters a neatly kept sitting room. On the walls are a portrait of Jesus Christ and quotes from the bible, carved into a wooden plate. A duck quacks noisily underneath the seats. Hannah, an 85-year-old woman, limps out of the kitchen door laughing. “That’s my duck, it loves that spot. My knees will not allow me to get down that low.”

Hannah was diagnosed with HIV 30 years ago, when she was working for a politician as a housekeeper. Her body increasingly weakened from the pain in her knees, back, elbows, wrists and head, and she could no longer make the trip to the politician’s home. “Waking up is a lot of work. It is so painful.” When she visited Kenyatta National Hospital for her pain, the doctors prescribed her Paracetamol (an ibuprofen equivalent painkiller), which does nearly nothing for the pain.

Hannah lives with her only grandson, who will be going back to high school soon. “My grandson is my everything,” she says. The boy’s mother died when he was young, so Hannah and the grandson have been supporting each other for over a decade. “But every time he goes back to school, I feel lonely again.” So Hannah goes to church and attends group meetings of Women Against Stigma, a support group for women with HIV/AIDS in Kajiji. Often, she needs help on the road. “If I could get proper painkillers, I would not depend on anyone because my hands and knees would be working again.”

Mary and Louise

On one end of Kajiji’s blue-and-green-tinted alley, Louise is stirring changaa, a whitish-transparent local brew, in a rusty pot with a wooden stick. It is noon, and the alcohol can be smelled from far away. A couple of men are sitting on the other end of the alley, drunk and unable to make sense with their words. Limping, Mary walks slowly down the alley. Having just sold some changaa, Mary comes back to her house, pats Louise on her back, and goes inside for a rest.

A single mother with four children, Mary’s life became a lot harder when she was diagnosed with HIV in 2009. Already living with high blood pressure, Mary struggles with pain in her joints. She says, “Sometimes my knees hurt; sometimes my elbows; sometimes my ankles; sometimes they hurt all together.” When she is in pain, she cannot work and has to stay in bed all day. “I visited some hospitals, and the doctors gave me some painkillers that would only last for a few hours. After the pills ran out, I was in pain again. I can’t work, and I can’t take care of my children. But at least Louise is helping us.”

Louise retreats into the shadow of the house to join Mary. She sits down quietly and remembers. “After I was diagnosed with HIV, my parents abandoned me. I was so scared of discrimination from other people that I lived in abandoned houses around Nairobi until Mary took me in. Now we brew changaa to sell in Kajiji for a living.” She gets up quietly and goes to stir the brew a little bit more.

Mary’s eyes fix on two aged, wooden field hockey sticks. She says, “My biggest pain is I can’t make enough money for my children. My big son is fifteen now and he loves to play field hockey. He is really good at it. But because I can’t pay his school fees, every week he will be chased out of school and then he can’t play.”

She picks up the hockey sticks and puts them close to her face. She suddenly starts crying, “I just wish the doctors could give me something strong so I have no pain. That way I can make more money for him to become a hockey player.”

Mary Auma

Mary Auma sits on her bed inside of her. Plastic bags of different colors are hung overhead, making the small room feel even more cramped. The afternoon light slivering through a tiny window highlights a scar on her left cheek bone.

A mother of three, Mary was diagnosed with HIV after community health workers where she used to live prompted her to have her sons examined. They were all diagnosed as HIV positive. That diagnosis cost her her job. “After they knew of my HIV status, they told me they do not need my services anymore.” She and her family now live in Kajiji, surviving on income from her odd jobs.

One of Mary’s daughters walks in. Mary holds her closely, continuing to tell her story.

In 2003, she was operated on for cervical cancer. She still suffers severe pain in her abdomen. After the operation, she visited Kenyatta National Hospital where the doctors prescribed ibuprofen. The pain was hardly relieved. The pain comes in mornings and on very cold days. When she is in pain, she goes to the local pharmacy where she can only get ibuprofen for mild relief. It makes her feel better for only a few minutes, but it is better than nothing. “I wish I could be free from pain. I would love to have my own business to provide for my kids and have enough money to take my older daughters to college.”

Regina

Through a dusty narrow path overgrown with pines and bushes, Regina finds her way back to the home that she calls “the hut in the jungle”. Regina retreated to Kajiji, its greener side, because of her HIV positive status. She was diagnosed in 1998, after her husband had left her.

Regine used to work at Woldof Kindergarten as a cook. After learning about her HIV status, the kindergarten laid her off. Since then, she has been living off bead work she does with Joyce and Doris from Women Against Stigma. When she experiences pain, she goes to Kenyatta National Hospital where the doctors prescribe Paracetamol (ibuprofen). Luckily, she has yet to experience severe pain.

Women Against Stigma has provided a community for her.

Susan

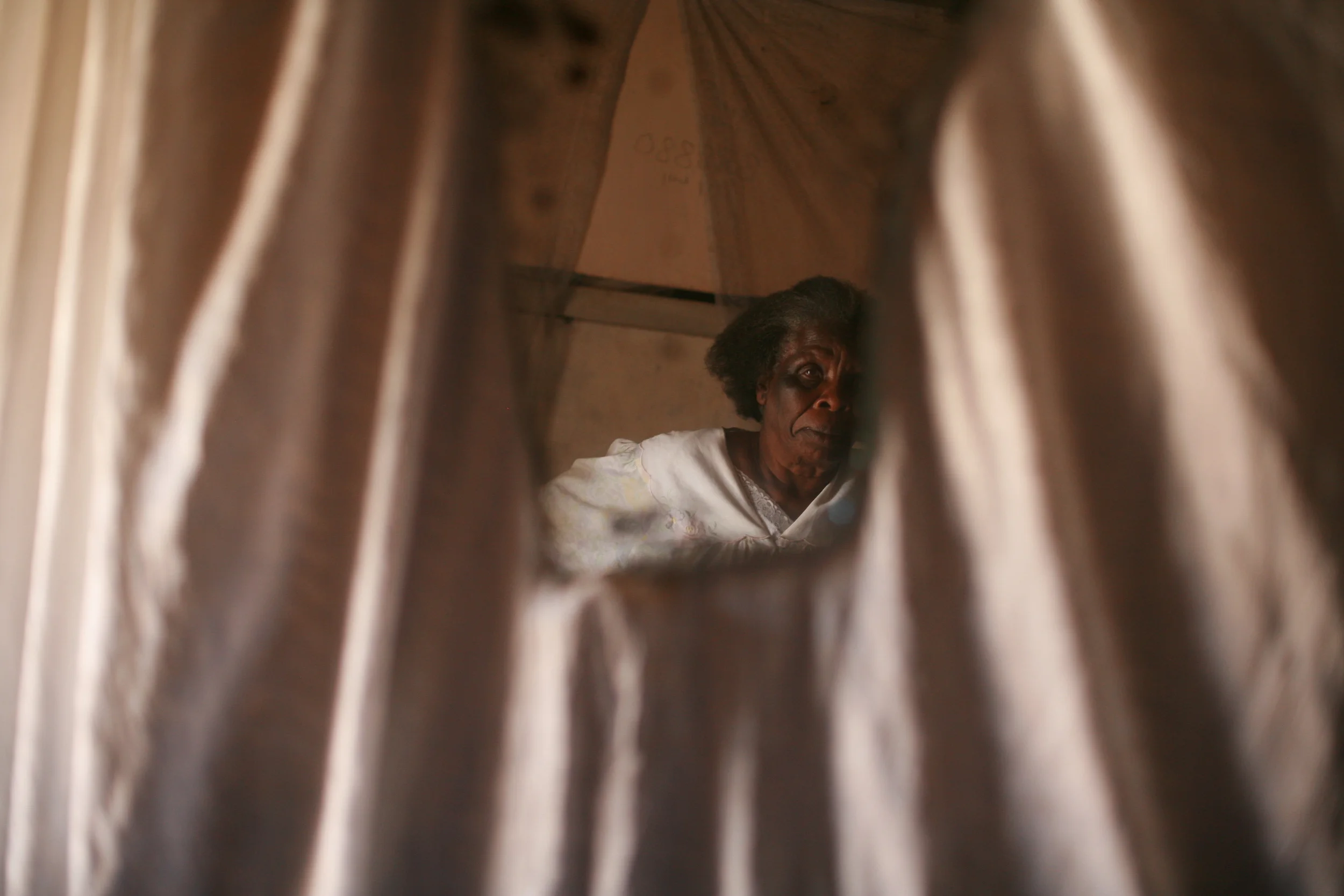

Susan sits on her left hipbone while supporting her weight with her right hand on a chair in her cramped home. The mosquito nets conceals most of the interior, leaving space for only a small couch and the armed chair where she sits.

In 1980, Susan fell into an open pit, a common form of toilet at the time in Kenya, and broke her hip and femur, the bone connecting the hip to the knee. She was treated at Kenyatta National Hospital, where her leg was put into a cast. Doctors told her all would be fine in a few months. They were right until last year when Susan began experiencing recurring severe pain in her hip. The pain prevents her from walking around, sitting and doing housework. “I visited a clinic here (near Lenana), the doctors prescribed Paracetamol. They didn’t tell me what’s wrong with me, and the drug didn’t work at all,” she says.

In the mornings and evenings, Susan experiences the most severe pain. “I wake up in pain and go to bed in pain. It is so painful that I can’t even describe it. Now I can’t work, and I have to rely on my family.”

“I just wish I could get back on my feet, and help with my family. Not sitting around all day in pain,” she said.

JOYCE and doris

Joyce:

Joyce emerges from hanging clothes and scattered toddlers. Under a navy blue bucket hat sits a bony face. She walks slowly and carefully into an empty yard and knocks on an old wooden door. When the door opens, she composes herself and begins her job.

Joyce was diagnosed with HIV a decade ago. After initially denying the disease, she made peace with it and started a small restaurant. Business was good until people starting talking about her and her HIV status, ending her business. The strong stigma that still surrounds HIV ended her only income. In response to the discrimination she faced, in 2007, she founded Women Against Stigma, reaching out to women who struggle with their HIV status. The goal was to help them lead a life free of discrimination. Although the organization established a community for local women, their work has not fully extended to the care these women need, such as basic health care, pain relief and palliative care focused on living with a chronic disease.

Like many other women she helps, Joyce also faces severe pain from taking anti-retroviral drugs (ARVs). On her way to see the next woman in pain, she murmured, “When I started the ARVs, I would see something scary coming to kill me. I would scream and scream. The hallucination has worn away, but my eyesight has deteriorated, and there is aching in my legs and my joints.” When she goes to clinics seeking to alleviate the pain, they only give her either weak painkillers, or nurses tell her there is nothing in stock. Many patients in Kenya are facing these same problems as painkillers for severe pain such as morphine is tightly controlled and not always available at public hospitals or much more costly at private hospitals and clinics.

Under the warm afternoon sun, Joyce looks down at the ground quietly and says, “One day, I thought if this is what I am going to live like for the rest of my life, I would rather overdose on my ARVs to death. The women and children I am helping are the only reason I am still alive.”

Doris:

Inside a blue-tinted gate, Doris lives with five other families. In the four meter by four meter room, white veils hung from the ceiling diffuse the bright sun from the window. Doris sits quietly and calmly shares her story. Beside her are her son, Evans, and her friend, Joyce.

Doris was diagnosed with HIV in 2003, when she was pregnant with Evans in Kenyatta National Hospital. “When the doctor told me about my status, I was in denial. I was suffering a lot both physically and emotionally. My aunt used to shout to everyone in the village about my status. She couldn’t even share a meal in the same plate that I was eating from. That was really painful.” Doris says.

Doris experiences a lot of pain as part of the side effects of the anti-retroviral drugs. “In the morning and on cold days, my joints become very stiff and painful. Sometimes I would forget things. I would forget that my son and I have already had the drugs, and we would overdose. In difficult times like that, I would go to Joyce who is always there for me.” She holds Joyce’s hand tightly as she speaks.

Doris is one of the very active member of the group Women Against Stigma in Kajiji. They raise awareness of the importance of checking HIV status for families, distributing condoms, taking the sick to hospitals and clinics, and coming up with business ideas for women whose lives are affected by HIV.

“My wish is to live a pain free life so that I could get a job, raise awareness of HIV, see Evans excel in school and join college and work towards zero HIV infection in Kajiji.”